Can new payment methods in health system affect quality of care?

By Francisco Londono, August 10, 1998

Introduction

For the purpose of this article I will make some generalizations

and I will define some words to facilitate the reading and understanding.

These definitions are not intended to be exhaustive and must be understood

only in the context of this article.

In America health has had its own evolution, passing

from the personal relationship between a physician and a patient to a complex

system with many actors. As technology developed, on one hand, the costs

increased and patients or their families weren’t able to pay by themselves.

As a consequence, new payers, such as Government and employers appeared

in the health industry. But once again, one treatment could be so expensive,

that the resources of a small employer wouldn’t be enough to cover it,

and his business could get in financial risk. Consequently, the typical

insurers began to play their own role: The affiliation of large number

of people paying a fixed premium per person and period of time, regardless

the cost of the treatments needed by each of their affiliates. A

patient could choose the provider, pay the treatment by itself, and later

the insurer reimbursed him the cost of it. If the number of affiliates

is high, the probability of a high cost treatment becomes more standard

or predictable and the excess of money the insurer earns with people who

pay and don’t get sick can absorb its costs. This is known as the “big

numbers” law.

On the other hand, physicians became more specialized,

and needed more technology not affordable on an individual basis. Now we

have physicians, nurses, hospices, clinics, hospitals and complex systems

joining all them in order to provide the care needed by patients. For the

purpose of this article I’ll call all of them providers.

Cost continued increasing, the relations between

these actors continued changing, and the characteristics of each of them

too. In the side of the insurers, in the 1980’s, the Health Maintenance

Organizations or HMO’s appeared. Despite their differences, in the beginning

most had similar characteristics: they were non-profit organizations providing

care to their affiliates with a selected net of providers and special rules

and procedures that patients and providers should follow in order to accept

the service and pay the provider.

Recently, in the search to achieve the key objective

of cost containment, the payment systems used have also changed. At the

beginning, the predominant way used by payers and insurers to pay providers

was a fee for each service they provided to a patient (fee for service

– FFS). The fees were defined sometimes by the provider, sometimes by the

buyer and other times by a negotiation between them. FFS payment system

had implied an economic incentive to providers in the form of being paid

more as more services were delivered to patients. Different efforts were

made to discourage the excessive cost. One of the best known, and still

in use, is the Diagnostic Related Groups (DRG's), where the provider received

a fixed amount of money for the complete care of a patient with certain

diagnose, despite the resources used in the care of the patient.

This helped, but was not enough.

Recent changes show that Medicare, to reduce its

expenditures, is shifting toward the affiliation of more people to health

care organizations (HMO’s). Medicare is paying HMO’s with a fixed amount

of money per person and period of time (per capita), equivalent to 95%

of the average cost of a Medicaid patient, instead of paying providers

directly. In this way Medicare could decrease its expenditures by 5%.

At the same time, in order to keep their costs down,

HMO’s are using new payment methods too. In addition to the traditional

FFS and DRG systems, they are sometimes paying providers in a per capita

mode, assigning a group of providers a group of affiliates and paying them

a percentage of the premiums collected from the affiliates. Sometimes they

only make contracts for some services so the per capita payment is rated

according to the scope of the services contracted. Other times, HMO’s give

economic incentives to reduce referrals, prescriptions or expensive treatments

to patients. If the total expenses of one group of affiliates exceed an

HMO established quantity, the providers are penalized and receive less

money or if they expend less than expected, they are better paid. The principal

arguments of the HMO’s to do so are: first, costs must be reduced, which

is generally accepted; second, the physicians are the critical decision

makers in term of costs, so they should have strong (economic) incentives

to reduce them; and third, it has been proven that many services are not

always necessary or are not cost-effective. Even though not all HMO’s are

the same, and not all of them use these kind of payment systems, I’ll use

the term of HMO’s in this article to refer only those who have these practices.

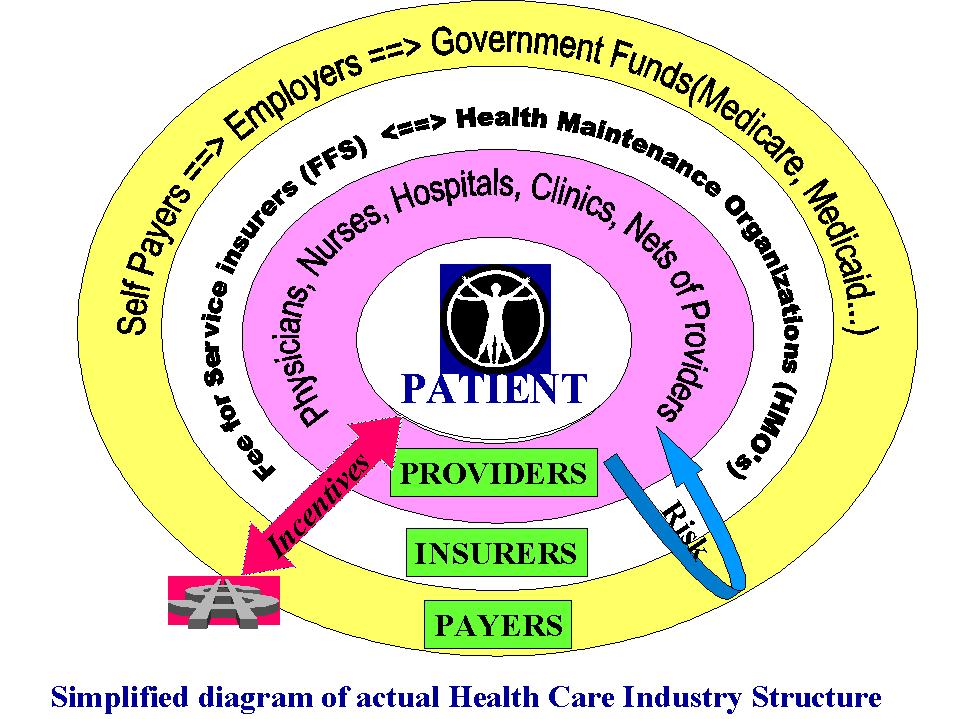

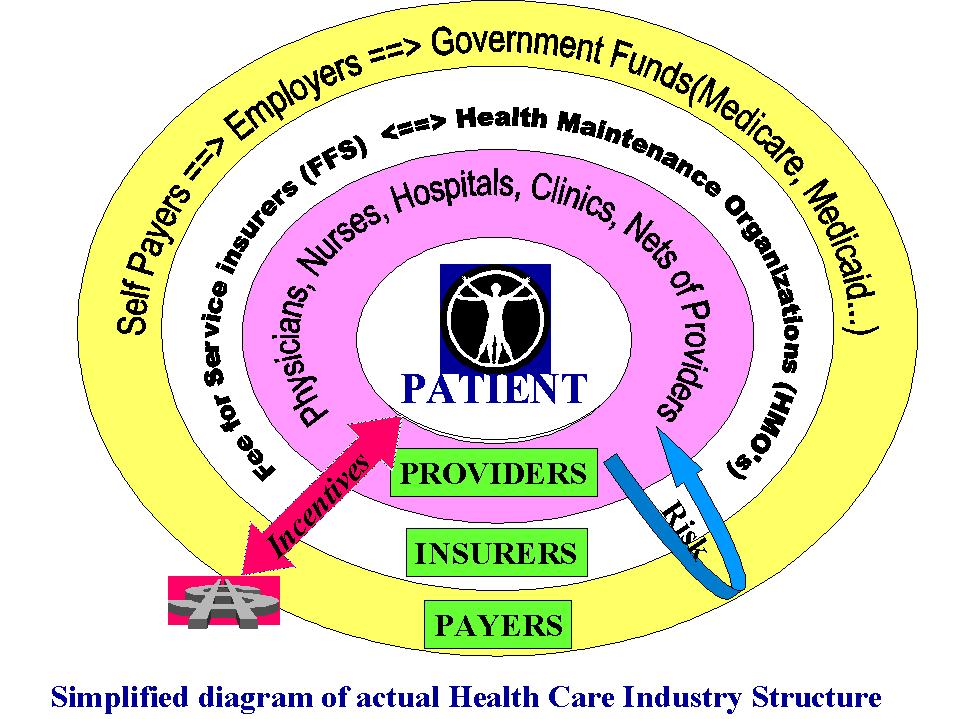

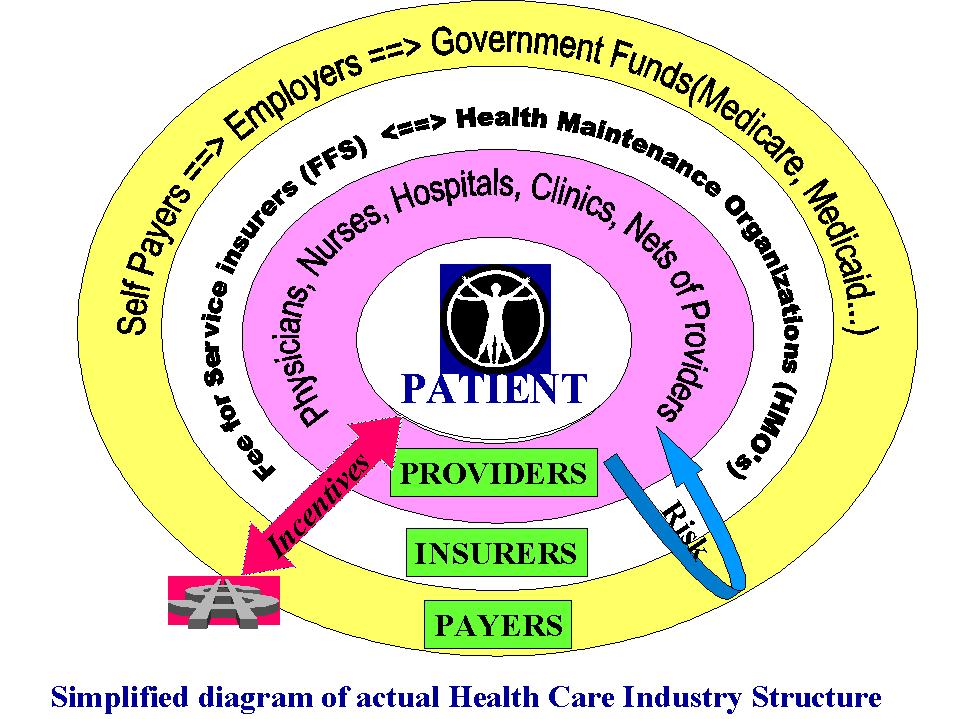

Next you will find a simplified diagram that depicts

how all this actors are integrated in a real more complex system than that

old one of the patient and his physician:

Principal questions about costs and quality implications

The purpose of this article is to analyze if these changes can affect the

costs and quality of care delivered to patients. Not all aspects of costs

and quality will be covered but some of the principal questions that have

emerged, some of the findings that have been done in the USA by some researchers,

and some conclusions will be given. The principal questions are:

? Are these new payment systems really helping to reduce costs?

? Whose costs are they helping to reduce?

? Do they affect the quality? How can they affect it?

? Are these new payment systems shifting the risk from the HMO’s to the

providers?

? Must we ask and answer ethical questions about incentives and similar

issues?

? Do different approaches exist to find a solution that helps to reduce

costs without affecting quality of care?

According to the importance of each question, all of

them will be addressed in turn.

Are these new payment systems really helping to reduce costs?

As the key objective of the new changes is cost control,

we must ask if the objective is being reached. Some findings directly related

to these new trends, show that they can really do it. A few of these findings

are:

-

For employers and self insurance buyers, it has been found that the rate

of increase in health care spending premiums has fallen from numbers higher

than 17% per year between 1987-1990 to near 2% per year between 1994-1996

(Hellinger, 1998). These findings show that at least the costs are not

growing higher than inflation as they usually did.

-

In his conclusions, Hellinger (1998:841) says “A recent review concluded

that the financial incentives for physicians are a key reason that managed

care plans have successfully reduced the use of health care services”.

-

Medicare is increasing the so called at risk contracts with HMOs at a fee

that represents 95% of the average Medicare spending per patient. This

new practice should help to reduce the cost of Medicare expenditures by

5%.

Whose costs are they helping to reduce?

As we saw in the last question, in many cases employers

and self-payers are finding savings or at least slow increments in their

premiums. Some researchers have found that the 5% cost reduction expected

by Medicaid is not going to happen. The principal reason for that conclusion

is that in some cases, HMOs are doing favorable selection to enroll healthier

people (Policy Information Exchange Online-PIE, 1996). In other terms,

even though is forbidden to reject the admission of a Medicaid beneficiary

in an HMO plan, they are targeting their marketing strategies toward healthier

people, such as younger people with good income. Bruce C. Vladeck, the

Health Care Financing Administration's (HFCA) Administrator commenting

on the study ‘Health Status of Medicare HMO Enrollees in 1994’ done by

the HFCA, said “This study clearly shows there still may be a problem of

risk HMO’s having healthier Medicare beneficiaries.” Later he also said

“These findings confirm again the need for a payment method that adjust

for the health status of Medicare beneficiaries who enroll in HMO’s.” (PIE,

1996). So, is Medicare going to save money this way? Probably not, because

the care for sicker people, and thus people more expensive to care for,

is still being paid directly to providers in a fee for service (FFS) way,

and their particular average cost must be higher. So, healthier people

costing Medicare 95% of actual expending average, and sicker people costing

more than the average, could make Medicare total cost rise. As Salins says,

HMO’s are “skimming the cream”. In this way, the HMO’s can keep costs down

the average and make profits. It is also known that some HMO’s have been

changed from no-profit to for-profit organizations.

Do they affect the quality? How can they affect it?

A primary question is how can these new ways of relationships,

with economic incentives to providers to control costs, affect the quality

of care? Before answering, a new question must be asked: What is quality

of care? There is no unique definition, but most authors recently included

in their definition aspects that not only concern the medical act itself,

but also the patient ease of access to the services needed and the general

satisfaction expressed by the patient itself. For the purpose of these

article I’ll only analyze these two factors.

Research has been done recently on this topic and

there is not enough evidence to have definitive conclusions (Hellinger,

1998:840). But some clues have appeared. As one critical aspect of quality

is ease of access, we must answer these questions: Is accessing in HMO’s

easier than that in typical insurers? Are the HMO’s accepting or denying

treatments recommended from providers to their patients? Can patients use

their preferred provider? In his revision of recent studies about ease

of access to care, Hellinger (1998:838) shows these findings:

-

Davis et al, 1995. “Enrollees in HMO’s were not as satisfied and had more

problems with access than enrollees in FFS (29% in HMO and 38% in FFS rated

plan as excellent; 26% in HMO’s and 45% in FFS rate access to specialty

care as excellent).”

-

National Research Corporation, 1996. “Enrollees in HMO’s had poorer access;

the percentage of enrollees in HMO’s who had no access problems (20.1%)

was less than for FFS (32.7%).”

-

Donelan et al, 1994. “Enrollees in managed care plans had poorer access.”

-

Brown et al, 1993, and Brown et al, 1993. “Medicare beneficiaries enrolled

in HMO’s were less satisfied and had poorer access than Medicare enrolled

in FFS.”

-

Nelson et al, 1996. “Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in HMO’s were more

than 3 times as likely to report access problems than Medicare beneficiaries

enrolled in FFS.”

Simultaneously, in recent years, as a response to the

increasing dissatisfaction and public claims about bad practice, more regulation

than ever has been made at state and federal levels, trying to protect

the people’s rights in access and quality of care (Dickerson, 1998). Laws

have been made to disclose the financial incentives that HMO’s offer physicians

to control costs, to give consumers the rights to a full appeal process

if denied treatment, to allow access to emergency-room care without previous

acceptance by the HMO, to grant minimum lengths of stay in hospital for

some treatments, to grant the continuity of plans from one HMO to another,

and so on.

As another clear answer to the permanent claims,

and a way to help people to choose between the different options, the Consumer

Assessment of Health Plans Survey (CAPHPS) is being developed. This study

is sponsored by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR),

the Harvard Medical School, RAND, and the Research Triangle Institute.

In this survey nearly 130,000 people are being asked about their own experience

with different HMO’s or FFS plans. People are going to score their service

in many ways, but the research will take time and the results are expected

in November 1998 (AHCPR, 1998).

Are these new payment systems shifting the risk from the HMO’s to the providers?

Another problem that providers complain about, is that

with the per capita payment system and with the reimbursement based in

an inverse relation to the cost of the attention provided (economic incentives

to reduce costs), HMO’s are trying to shift the risk directly to the provider.

As explained in the introduction, one of the key principles of insurance

is the general law of “big numbers”. A patient’s treatment can be

so expensive that it can consume the resources of many patients. If the

group of patients is small, all patients’ premiums can be consumed and

the HMO or the provider loses money. If the group is large enough, then

the looses are much smaller. In general, providers joined in nets or alone

don’t have the same number of patients, and their risk is higher than that

of the HMO’s. As Salins says, shifting the risk to the providers, HMO’s

play a zero-sum game. They can assure profits and minimize almost to zero

the risk of looses. In his article, Salins also suggests that as providers

are taking risks, they are also beginning to do favorable selection. Some

teaching hospitals that typically have searched for the sickest people

in order to learn more are beginning to express their worries, because

if they continue doing the same way, and are being paid with the new systems,

they will no longer be able to cover their costs. So, who is going to care

for the sicker people? Once a provider or group of providers has over passed

in cost the reimbursement, who is going to pay for the services still needed

by patients? Can the provider absorb looses or are they going to refuse

treatments or services in order to survive? If the risk is going to be

shifted to the provider why do we need insurers, and of course why do we

need more actors to be paid in the chain of the health care industry?

Must we ask and answer ethical questions about incentives and similar issues?

Another key issue, very difficult to be studied with

numbers is the ethic question that physicians and providers have to ask

themselves frequently. What is first, the health of the patient or my income?

The answer seems very clear in the perspective of ethics, but what about

this other related questions: Is the prescription really needed? Are there

better options? Are better options more expensive? Are there other cheaper

options? Do they have the same risks? Are cheaper options well tolerated

by the patient? What level of treatment tolerance by the patient is desirable?

What is the right definition of cost effectiveness? What is the tolerable

level of effectiveness that a treatment must have in order to be accepted?

Is the use of pain control treatment worth it on a terminal person? and

so on. As medicine and health care are still not exact sciences, and the

concept of health is not unique and universal, many questions do not have

a clear answer, but providers have to make decisions on a day to day basis,

now.

Do different approaches exist to find a solution that helps to reduce costs

without affecting quality of care?

One of the best contributions that the HMO’s, the insurers

and the providers can make is just in progress, and all of them are working

hard to find “best practices” on health care. The information that can

be gathered today is not still completely used as it should be. Best practices,

if managed well, can help simultaneously to improve quality and reduce

costs. Health is not the exception to one of the principles of quality:

Quality costs less. We must not expect an exact answer to treat each different

illness in each patient, but Pareto’s law also applies to health. Most

costs are consumed delivering care to patients with a few common diseases

(Pareto’s law says < 20%). If we learn to treat well these few diseases,

we can increase quality and reduce costs. New studies of what is called

Evidence Based Medicine are in progress and they are going to help to decide

what treatments are the most indicated for the most important diseases.

Simultaneously with the support of the HCFA, new

approaches combining the FFS payment system with the Group-Specific Volume

Performance Standards (GVPS) are in progress. This new approach takes advantage

of giving economic incentives to providers based on quality of care and

the use of standards instead of using direct cost reduction incentives.

This approach would permit patients the freedom to choose the provider.

Also the providers could be paid on a FFS basis and be encouraged to use

cost-effective service delivery patterns (Tompkins et al, 1998).

Conclusions

According to the findings, accepting that the evidence

is not as complete as anyone should desire, and taking into account the

questions that are being made, some conclusions are:

-

More research is urgently needed in all these topics. Current research

studies and their findings are not enough. Sometimes this kind of research

is as complex and time consuming, that when the results are available things

have already changed. Although we can learn which things were done

good, which were not, which are the risks involved, and which must not

be repeated. Once you forget history you repeat the same mistakes.

-

Economic incentives to the providers are very dangerous in the field of

health. They can promote either over-treatment to increase providers’ benefits

or deny care needed to increase HMO’s profits. Many ethical questions have

to be asked and answered.

-

While incentives exist as they do today, effective controls must be designed.

Politicians, control agencies and all the health industry actors should

develop new laws to protect patient rights and prevent abuses. They are

not going to be perfect and there is no unique solution, but we have to

act right now.

-

The health market is known as an imperfect market, and the principal reason

is the information available to the actors. So, it’s important to support

the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey (CAHPS, 1998). This will

help users to make a more reasonable and informed decision.

-

Hybrid approaches combining the use of information, GVPS standards and

FFS payment system must be encouraged strongly.

Finally it’s clear that the evidence available it is

still not enough to make definitive conclusions. However life is going

on, decisions are being made and must be made. Just with the scarce information

available today we have to make the right decisions, trying to decrease

the risks involved, and at the same time answering, in the most acceptable

way, the questions that have emerged.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR). (1997).

Consumer assessment of health plans (CAHPS): Fact sheet.

Available: http://www.ahcpr.gov:80/qual/cahpfact.htm. [1998, 16 July]

Dickerson, John. (1998). Lets play doctor. Time, 152 (2), 28-32.

Hellinger, Fred. (1998). The effect of managed care on quality: A review

of recent evidence.

Archieves of Internal Medicine, 158, 833-841.

PIE Online. (1996). Medicare risk HMOs experiencing favorable selection.

Available: htto://mimh.edu/TM/e26304T3777. [1998,7 July].

Tomkins, C; Wallace, S.; Bhalotra, S.; Chilingerian, J.; Glavin, P.;

Ritter, G &

Hodgkin, D. (1996). Bringing managed care incentives to Medicare’s

fee-for-service

sector. Health Care Financing Review, 17 (4), 43-63.

Salins, Craig. The new faces of “Managed Care.” Available:

http://www.peak.org/~ramselj/salinxx.txt. [1998, 2 July].